CURRENT RESEARCH

Nohoch Batsó

The Mountain Pine Ridge Forest Reserve is one of the few areas of the eastern Maya Lowlands that remains relatively unstudied by archaeologists. At the end of our 2019 field season, we made an unsuccessful trip to relocate Rio Frio Cave E. Though we never made it to the cavern, on our way home, we walked into a Maya settlement that was unknown to archaeology. When new sites are discovered in Belize, the archaeology team gets to name them. We named the site Nohoch Batsó, meaning Big Monkeys in Yucatec Mayan. Because of COVID, we had to wait to start our research here until June 2022. Being the first investigations of a Maya settlement in an relatively understudied region of the pre-Columbian Maya world, we set out to answer basic research questions about it. When did people live there? When was it first settled, and when was it abandoned? What was its relationship with other sites in bordering regions like Minanha, Pacbitun, and Calendonia? What about sites further away like Caracol, Cahal Pech, Baking Pot, and Xunantunich? Being the closest-known site to the granitic rock outcrops that were the favorite source of rock for sites throughout Belize and adjacent regions of Mexico and Guatemala, did the rulers from Nohoch Batsó exert control over the resource and its distribution? These are just a few of some of the many questions we have about this site as we start out research there. More are certainly to arise as we continue our work there.

Buffalo Hill Quarries

Archaeologists have long known that the Mountain Pine Ridge was a primary source of vital resources necessary for ancestral Maya daily life. Resources such as granite and other kinds of rocks, pine wood, and prey animals are all found there. Moreover, the Mountain Pine Ridge is one of the few places in the Maya lowlands where these important resources were found. Although the artifacts the materials were used to make are familiar to archaeologists–manos and metates, mirror backs, stelae, incense, and more–we know very little about how these raw materials were harvested or how the objects were made. In the case of the granitic rock quarries, were they being worked by people living locally, or by visiting groups from other sites in the region? In addition to who they were and did they make the tools, what were their daily lives like? What did they do for food, where did they spend the night? Were they living in temporary camps or semi-permanent homes? Was control over the resources, and the production and distribution of final products centralized or decentralized? We also know that many Maya people today consider natural resources to be owned by a being commonly referred to as the Earth Lord. Whenever someone wants to use some of the Earth Lord’s possessions, they must make a petition to him and a ritual of thanks afterwords. Were similar rituals being performed in the past for the quarry workers?

Rio Frio Cave A (AKA Twin Caves)

Although excavated originally in 1928 by Gregory Mason, little was published about the work (see the tile to the right). We have recently located part of the artifact collection at the Smithsonian Institution, and are trying to learn where the remainder is located. The cave is full of architecture and artifacts are still scattered all over the floors. Our aim is to learn when this cave was used, who was using it, and for what purposes? In the Summer of 2019, we began excavations here to address those questions. Our studies revealed the cave was first used in the Late Preclassic period (starting around 300 BCE) and continued to be use regularly throughout the end of the Classic period (approximately CE 250-900). Nonetheless, our research strongly suggests earlier and later use is likely. Several small, charred corn cobs suggest agricultural rituals were performed in the entrance. Unfortunately, the cave has been severely damaged by modern graffiti. One of the ways we are studying this cave and aim to preserve it in its current state for future generations to enjoy is through the creation of digital models and virtual tours which you can view in the “Virtual Rio Frio” section of this website.

History of Archaeology of the Rio Frio Caves

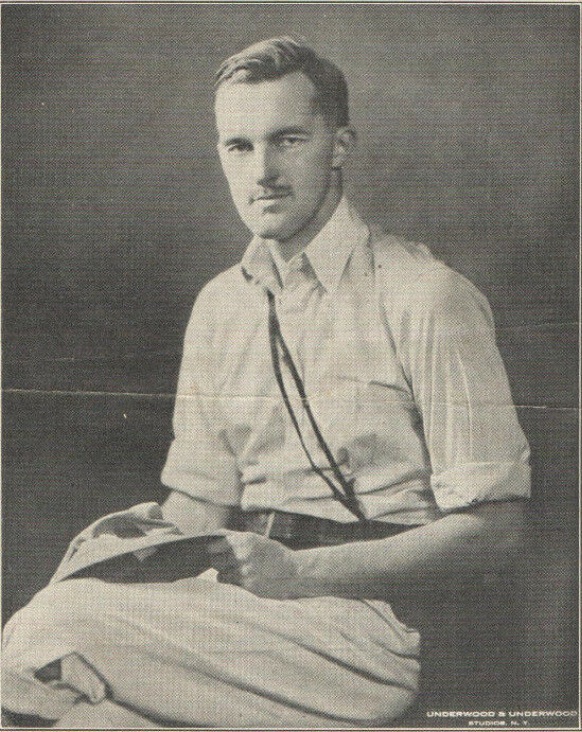

Though the COVID pandemic prevented us from getting into the field in 2020 and 2021, we were able to continue our research of the Rio Frio Caves. We began by making a close reading of Gregory Mason’s 1928 “Pottery and Other Artifacts from Caves in British Honduras and Guatemala.” That publication marks the first scientific documentation of the Rio Frio Caves. Mason excavated and made extensive collections in all three, but his publication lacked maps and the photographs were largely limited to the whole vessels he recovered. Luckily, he provided decent descriptions of the areas where he worked, and we have been using our virtual walking tours of the caverns to piece he work back together. Check out our recent talk given to the Institute of Maya Studies in the “Publications and Presentations” section of the website to learn more about this part of our project.

Mason’s trip to the Rio Frio Caves was made as part of the Mason-Blodgett expedition out of the Heye Foundation – Museum of the American Indian in New York, which is now part of the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington D.C. We recently traveled to the NMAI to begin studying this collection for the first time and fully documenting it to contemporary archaeological standards. We have been able to verify that at least half is in the Smithsonian, and the other half was likely shipped to the British Museum in 1929.

Domingo Ruiz Cave

This cave first came to our attention in December 2018, soon after it had been opened for tourism. We began our investigations of the cavern a year later in December 2019. Like our work in Rio Frio Cave A, our research is focused on basic questions about the site; when was it used, who was using it and for what purposes. Our aim in studying this cavern in conjunction with Rio Frio Cave A is to begin understand the regional pattern of cave use. One pattern that has become increasingly clear is that the caves of this region are filled with architecture, both large and small scale. In the case of Domingo Ruiz cave, much of the architecture at the entrance seems to be designed to limit the amount of sunlight reaching the interior chambers. Walls, terraces, and stone alignments abound. To date our investigations include only a few test units for chronology, but we aim to start up work here again in the coming seasons.

Waterfalls and pools

Anthropological studies of cultures world wide report that waterfalls are nearly universally revered as powerful places. The Mountain Pine Ridge is home to many waterfalls and pools, such as the Rio On pools, Big Rock Falls, Pinol Falls, Thousand Foot Falls, and countless others. With many cave sites and important rock outcrops near them, ancenstral Maya people were undoubtedly aware of these beautiful spots. Yet, such places are few in the Maya world and we will be investigating these well known tourist places to search for shrines and other evidence of the relationships ancestral Maya people may have had with them.